Ware's bridge: a brief history

S Williams

There is evidence that the Romans crossed the river by the lock but the bridge came to be in its present position due to some Norman town planning.

The town centre was developed in the 12th and 13th centuries by diverting a road down Baldock Street and running it parallel to the river along the line of the present High Street before crossing the river at Bridgefoot. This meant that travellers had to pass through, but would stop and spend money. Ware was partly under the control of the bailiff of Hertford Castle and forced to hand over tolls from the bridge, which the townsfolk resented. It was a long and sometimes violent dispute. In 1191, Hertford men broke up the bridge to divert traffic to Hertford and the Ware men responded by ‘breaking their heads’. By the late 13th century, Ware was the main crossing between London and the North East but the rivalry between the two towns went on well into the 20th century.

In 1464, the bridge tolls were let to Thomas Cock for £25 a year, (worth around £16,000 today) and in the early 1500s to Fulk Walwyn. In 1667, William, Earl of Salisbury was indicted for ‘neglecting to repair a common cart-bridge in the parish of Ware, in the highway there’. It was referred to in the late 16th century as being arched and made of stone, which was uncommon at the time. After the stone bridge went, it was made of wood.

Dangerous and dilapidated

It was rebuilt many times and was often in a dangerous state. In 1788, the Gentleman’s Magazine recorded that ‘in the evening, as the St Ives Waggon was passing over Ware Bridge, just as the horses were over, some of the planks gave way and let in the waggon. Fortunately, the pole pin, breaking in an instant, disengaged the horses and the waggon and its contents received into an empty barge beneath the bridge. All was recovered except the hind wheels, which flew off and sunk. The bridge was new, built of timber, not above 25 years ago’.

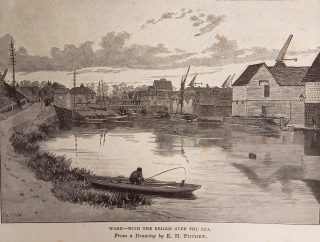

In the 1830s, it was described as ‘wooden and very ancient’, resting on piles driven into the bed and on abutments of brickwork on the banks on either side. Attached and resting on piles was a small house, used by the person who collected the tolls in the parish of Great Amwell. (The toll house and its attached privy can be seen on the map of 1843; the street called Amwell End used to be part Amwell parish). In 1835 it was referred to as ‘long been in such a dilapidated state’.

In November 1843, the Hertfordshire Mercury reported that the ‘unsightly and dangerous bridge at Ware’ was to be replaced by a ‘handsome and convenient structure’. The quaint toll house beside it caught the eye of Queen Victoria who was passing through the town. She was reputedly interested in the carvings around the doors and was dismayed to hear of it’s imminent demolition, along with the old bridge and its ‘picturesque palisades’. True or not, she was told the carvings were the work of bargemen, using knives meant for bread and cheese. An artist was commissioned to make drawings of it but its unknown where they are or if they have survived.

Its seems that no-one was confident about the state of it – when the viaduct bridge was being built in 1843 for the railway, the County Press newspaper said ‘the crazy old Ware Bridge which it was hoped would give place to some more suitable scheme, will, it seems not be touched in consequence of the refusal of the Marquis of Salisbury to allow it to re-built’. Presumably the Marquis was unhappy about the potential loss of income (his ancestors had been collecting tolls since the 1620s). Someone in the 19th century described it as ‘vexatious since time immemorial’.

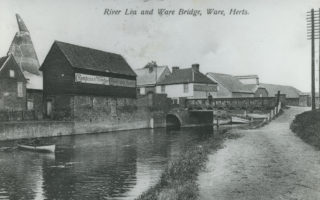

In 1845, an iron bridge by G Stephenson replaced the old one at a cost of £2,000 but even by October 1858 no-one would stand on it in case it collapsed when ‘Romaine’s Steam Cultivator’ (described at the time as a ‘Monster Machine’ came into town on its way to Royston. It weighed 12 tons and made the ground vibrate. There were various versions of the bridge until the 1960s when it was widened to cope with the increasing traffic. Part of the 17th century Old Crane pub was demolished along with it.

Tolls and fights

By 1824, the bridge was let at an annual sum of £20 – according to an open letter in the newspaper, it was put up for auction and, to the annoyance of locals, a ‘body of toll hirers came up from London and bid £500’ for it. Riot and confusion ensued and the new owners were refusing to let anyone pass unless they paid a heavy toll. It was also claimed that the Bow Street Runners would be coming to the bridge to keep order and if it was worth £500 to a private individual, the least they could do was build a new and safer bridge. The toll was collected from all who had vehicles or cattle if they were non-residents coming from the Amwell side.

Being a toll-keeper would have made you unpopular. In June 1845 Joseph Camp of Hertford was fined 1s and costs for assaulting the keeper. Camp claimed exemption from the toll as he drove a spring cart (a one- horse, two-wheeled vehicle). The gate was shut and Wheatley, the keeper, got hold of his horse to allow another vehicle to pass, so Camp hit him with his whip.

In 1855, Francis Gibbs was the collector and he was charged with using insulting language towards William Kite on the bridge after a dispute over payment. In 1865, George Sharp, a carter from High Cross was was charged with assaulting Thomas Cass, the keeper. He refused to pay for extra loads and ‘struck Cass several times’. John Chapman was also fined in June for using ‘very vile language’ on the bridge.

Thomas Cass, who was blind in one eye, died on the bridge in November 1878 after being hit by a cart. He was 54 years old. His wife, Ellinor Cass continued to collect the tolls and one day, she was assaulted by Edward Mellish, a baker from Westmill who pushed her over after she deliberately shut the bar when he refused to pay. In 1882, Cass’s successor, Thomas Cook was fined by the court. Sergeant Hammond said he was ‘drunk and acting stupidly on the bridge’. Cook said he was ‘on his own doostep’ but Hammond said he wasn’t and that he kept coming out of his house to make a noise and attracted a crowd.

Its legality had been questioned for years, but the tolls continued to be collected until 1899 when the County Council and Ware Urban District Council bought the bridge from the owners for £100 – they congratulated the town on being free of the ‘vexatious burden’.

Accidents

There would have been many accidents on the bridge over hundreds of years and local newspapers from the 19th and 20th centuries are full of incidents:

Fire at the toll house and death of the keeper (Herts Mercury 18 Feb 1843)

‘At an early hour flames were observed from the road of the dilapidated toll house on the Ware bridge which excited some alarm, lest the solitary inmate should have sustained injury. The door was broken down and the toll-keeper was found sitting on a chair asleep and enveloped in dense smoke, which must have suffocated him. The fire is supposed to have been occasioned by a candle. The old toll house now presents a more forelorn appearance than ever.’

In May 1865 there was a night time crash between a carriage and the Welwyn mail cart – the mail had no lights and the carriage overturned, seriously injuring the driver. Alfred Aylott, aged 44 from Watton-at-Stone died in 1885 after he was dragged by his horse over the bridge following a collision.

Some people fell in by accident and drowned at the bridge, or died elsewhere along the river but were found there. In 1836, Thomas Burr, a blacksmith got into trouble and drowned by the bridge after a bet, but passers-by didn’t try to save him as they couldn’t swim. Some had a lucky escape, such as William Clibborn, aged 52 who charged with attempting to commit suicide whilst ‘in a state of intoxication’ in September 1885. He was described as ‘dejected looking’ and witnesses said he had already tried several times that day. Clibborn was fined for his attempt, the court having no sympathy (and suicide was illegal). In June 1887, Hiron Hammond, a bargeman was summoned for undressing and attempting to jump off the bridge in the middle of the night. He was let off with a caution for his ‘silly attempt’.

Nuisances and misdemeanours

In the 1620s, James Game, a labourer was in trouble for dumping dung and straw by the bridge in Amwell End, ‘much to the annoyance of the highway’. In March 1855, Amos Day was charged with leaving his horse and waggon on the bridge and was fined for it. In February 1856, 12 year old John Reeve was fined for playing hockey on the bridge, a practice which had ‘become a nuisance of late’ due to breaking windows. In the 1870s there was even a notice there to say that anyone caught ‘loitering and obstructing the footpath would be dealt with by the law’. The law was clear: pay a heavy fine or go to prison for seven days’ hard labour.

Foul, fetid and rank

Pollution was also a major problem as in December 1864, the Inspector of Nuisances observed a ‘black oily scum all over the river by the bridge which was fermenting with bubbles of gas and seething putrid mud by the banks.’ Domestic and industrial waste went in the river and during the summer months the smell would have been terrible. The Lea had a bad reputation in general, in 1887 a poet wrote ‘tis but a narrow unclean ditch at best, where murdered dogs and cats are left to rest’. Punch Magazine called it ‘foul, fetid and rank’ and in 1885, a music hall singer sang about poisoning his wife with the water from it.

A pub on every corner

In the early 1900s there were still four pubs in the corners of both sides – The Saracen’s Head on the High Street, The Barge on the corner of Star Street and The New Bull and the Victory (also known as the Ship) on the other, where you could have a drink on the towpath. They had all been demolished by the 1960s, the Saracen’s Head being the only survivor, albeit in a new building.

It was said that Ware men had warts on their tummies due to all the time they spent leaning on the bridge…

Add your comment about this page

Ware Pubs, “The Crane” stood beside the old bridge and was demolished in 1843 to make room for the new bridge and Viaduct Road. “The Bull” would have been built about late 1840’s

As a former resident of Amwell End, I am interested in the older pubs or places with accommodation referred to in Edith Hunt’s book, such as the “The Admiral Vernon”, “The Fox” & “The Pipe and Pot”

Would appreciate any help with these

Regards Tony Burgess